One of my students recently asked about the origins of 'OK' and whether it had started out as an actual word before becoming the easily-texted acronym used by speakers and non-speakers of English, alike. The answer turns out to be much more americana than i would have guessed. It started with an 1838-39 New England slang fad which was then appropriated by the re-election campaign of the 8th US president, Martin van Buren, known by supporters as 'Old Kinderhook,' a man who supported forced removal of the Cherokee’s in spite of having written ‘The government should not be guided by Temporary Excitement, but by Sober Second Thought.’ According to etymology online:

Van Buren lost [the election], the word stuck, in part because it filled a need for a quick way to write an approval on a document, bill, etc. The noun is first attested 1841; the verb 1888. Spelled out as okeh, 1919, by Woodrow Wilson, on assumption that it represented Choctaw okeh "it is so" (a theory which lacks historical documentation); this was ousted quickly by okay after the appearance of that form in 1929. Okey-doke is student slang first attested 1932.

Woodrow Wilson probably needed an innocuous term like 'okeh' after getting re-elected in 1916 under the banner He Kept Us Out of War and then asking the US Congress in 1917 for a declaration of war. 'The world must be made safe for democracy.' Indeed, to this day the inhabitant of the Oval Office believes 'it is so'. Another source adds Teddy Roosevelt to the presidential mix:

"O.K." (aka "okay") originated with US President Teddy Roosevelt, when his staff would inquire to him "How's everything today?", he would reply "Just like at Old Kinderhook." Old Kinderhook was a camp that he had attended during his childhood with great memories. [ed. Both Van Buren and Roosevelt came from the same area in New York State.]

while yet a third source tacks on this bit of proletarian trivia: 'Greek immigrants to America who returned home early 20c. having picked up U.S. speech mannerisms were known in Greece as okay-boys.' One small piece of slang, one expansive foray into American history. At least we can say this is one word from their rebel colonies that the Brits don't seem to have had much trouble assimilating into their more pristine anglais.

Lastly and my personal favorite: kseroks. Any guesses? Having lived outside the US for nearly a decade now, i rarely hear this word used anymore and once i learned what it meant, have kept my eyes peeled for an actual Xerox-made copy machine. Sightings? Zero. Assuming the vast majority of Azeris don't know that Xerox was the original photocopy king of kings, i'm left wondering what they think about the source of this word for 'photocopy'. KƏNIN would have made a lot more sense, if we're thinking along the lines of Hoovering, Ajaxing and having kleenex on hand for those sentimental Kodak moments.

Lastly and my personal favorite: kseroks. Any guesses? Having lived outside the US for nearly a decade now, i rarely hear this word used anymore and once i learned what it meant, have kept my eyes peeled for an actual Xerox-made copy machine. Sightings? Zero. Assuming the vast majority of Azeris don't know that Xerox was the original photocopy king of kings, i'm left wondering what they think about the source of this word for 'photocopy'. KƏNIN would have made a lot more sense, if we're thinking along the lines of Hoovering, Ajaxing and having kleenex on hand for those sentimental Kodak moments.

For me, this is something of a double whammy: i've always thought it absurd to use a machine maker's name for the thing the machine produces and now i've got to use the name with a spelling that has no relation to it, whatsoever. The orthography here is totally screwing with the etymology and i just don't like it, not one bit.

For me, this is something of a double whammy: i've always thought it absurd to use a machine maker's name for the thing the machine produces and now i've got to use the name with a spelling that has no relation to it, whatsoever. The orthography here is totally screwing with the etymology and i just don't like it, not one bit.

There's an Australian aboriginal character in one of Herzog's films who confesses that the reason he stopped speaking was because the slow genocide of his tribe left him with no one who spoke his language. Honestly, there are moments when i feel that way, a slow descent into a globalized transliteratory and mis-translational hell. In Hungary, hello is now part of the everyday language, which sounds graciously anglophilic until you realize they use it at the end of a conversation, not the beginning. i'll never get used to that, anymore than i will looking for a place to kseroks some documents. i'm all for diversity and mashing things up, world music and intergallactic web servers, etc. etc. but the words still have to mean something! Otherwise, our thoughts become temporally exclusive and watered down across cultural boundaries to the point where we're all negating our identities in order to communicate basically nothing. What would Homer say? Okay? OK? Okeh?

In college, i had a Medieval Chinese History professor who was passionate about the way Chinese philosophical history was embedded in the stroke patterns of the language's characters. The concept of orthography as a carrier of cultural development was at that time somewhat new to me, but as a would be writer and avid (painfully verbose) talker, i've since been attempting to do a respectable dilettante's job of catching up, academically. There are so many ways to communicate and absorb ideas - i often perceive concepts as manifestations of Flatland-like, geometrical relationships; some people understand things clearly through color, or sound - if language is going to convey interpretive, cultural meaning and to assign values to things both objectified and abstract, then the words we use to construct them need to consist of more than just phoneme tags. CUL8R is cute and all - i certainly enjoy letter-digit symbology - but it's important to me that people remember this is symbology, that the meaning is based on actual words which have linguistic histories, that those histories are far from random even if the phonetics are not.

Living in Azerbaijan these past few months, i've constantly found myself caught in a tug of war between orthography and meaning. The Azeri language, a member of the Turkik (Altaic) language family, is a fascinating amalgam of tongues that together reflect the full gamut of historical experience: invasion, conquest, expansion, integration - back and forth, on and on - such that we find today significant overlap with Turkish (Turks insist they can speak and understand Azeri perfectly; Azeris insist it's the other way around; neither are completely at ease using the term Azeri Turk as a modern identitfier for the people now called Azerbaijani); there are French words acquired through Russian, Russian acquired through years of CCCP integration (and probably, cyrillization of the Azeri script), Arabic words that came through Persian and some modern Farsi appropriations, as well (Azeris tell me these words are Turkish, but then where did the original Muslim-conquered Turks get them from?). Add to this the variety of local tribal idioms (see Dance Kavkaz) and you get a modern language that contains about 1500 years' worth of linguistic influences. Is it any wonder the national lexicographers have apparently taken the attitude that if they spell it Azeri, they make it Azeri? (Anyone reading this who takes offense, i'd be happy to discuss it with you over a nice biznez lunc, will even bring my ofis manejar along as backup translator.)

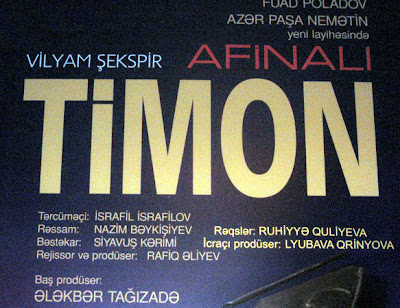

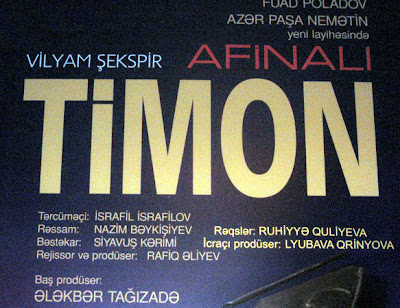

There is an acute difference between making language fun and making language funny. For me personally, orthography - like emoticon/texting symbology - mostly falls into the latter category, though sometimes i see transliterations that make my inner indo-europeanite cringe. Take, for example, this theatre poster for an Azeri adaptation of Shakespeare's Timon of Athens.

According to wikipedia, the Old German is Wilhelm and Old Norse, Vilhjálmr, bringing us as close to the Azeri spelling as Anglo-Norman Williame, but for someone who wrote with the sharpest of pens, this transliteration of Shakespeare strikes me as - i don't know, silly, i guess. Way too far afield. However, the thing about proper names is that if you want people to say them more or less correctly in their own language, you've got to make allowances for extremely different letterings. Sekspir. Fair enough.... whatever.

According to wikipedia, the Old German is Wilhelm and Old Norse, Vilhjálmr, bringing us as close to the Azeri spelling as Anglo-Norman Williame, but for someone who wrote with the sharpest of pens, this transliteration of Shakespeare strikes me as - i don't know, silly, i guess. Way too far afield. However, the thing about proper names is that if you want people to say them more or less correctly in their own language, you've got to make allowances for extremely different letterings. Sekspir. Fair enough.... whatever.

According to wikipedia, the Old German is Wilhelm and Old Norse, Vilhjálmr, bringing us as close to the Azeri spelling as Anglo-Norman Williame, but for someone who wrote with the sharpest of pens, this transliteration of Shakespeare strikes me as - i don't know, silly, i guess. Way too far afield. However, the thing about proper names is that if you want people to say them more or less correctly in their own language, you've got to make allowances for extremely different letterings. Sekspir. Fair enough.... whatever.

According to wikipedia, the Old German is Wilhelm and Old Norse, Vilhjálmr, bringing us as close to the Azeri spelling as Anglo-Norman Williame, but for someone who wrote with the sharpest of pens, this transliteration of Shakespeare strikes me as - i don't know, silly, i guess. Way too far afield. However, the thing about proper names is that if you want people to say them more or less correctly in their own language, you've got to make allowances for extremely different letterings. Sekspir. Fair enough.... whatever.Next up, the sign over a home furnishings store. Aksesuarlari? Hungarian speakers will immediately relate to the ler/lar plural form, which leaves us with aksesuar as the base noun. From the French accessoir, originating from Latin accessōrius: moving to adapt, towards accepting subordination, etc. etc. starting with the initial prefix, ac-. i really don't want to come across as being totally anal about word derivations, but as any fashion queens knows, it's all about making the little pieces come together. For Azeris out to accessorize their home furnishings, what significance could this word possibly have? i'm sure they got it from the Russians, but given the different alphabet, how would a non-russophile know that? The word thus takes on an objectified meaning based on - well, nothing beyond what's available in the showroom. Put this together with mebel, akin to Spanish mueble, and we immediately sense the profundity of res mobilis, res vilis.

Lastly and my personal favorite: kseroks. Any guesses? Having lived outside the US for nearly a decade now, i rarely hear this word used anymore and once i learned what it meant, have kept my eyes peeled for an actual Xerox-made copy machine. Sightings? Zero. Assuming the vast majority of Azeris don't know that Xerox was the original photocopy king of kings, i'm left wondering what they think about the source of this word for 'photocopy'. KƏNIN would have made a lot more sense, if we're thinking along the lines of Hoovering, Ajaxing and having kleenex on hand for those sentimental Kodak moments.

Lastly and my personal favorite: kseroks. Any guesses? Having lived outside the US for nearly a decade now, i rarely hear this word used anymore and once i learned what it meant, have kept my eyes peeled for an actual Xerox-made copy machine. Sightings? Zero. Assuming the vast majority of Azeris don't know that Xerox was the original photocopy king of kings, i'm left wondering what they think about the source of this word for 'photocopy'. KƏNIN would have made a lot more sense, if we're thinking along the lines of Hoovering, Ajaxing and having kleenex on hand for those sentimental Kodak moments. For me, this is something of a double whammy: i've always thought it absurd to use a machine maker's name for the thing the machine produces and now i've got to use the name with a spelling that has no relation to it, whatsoever. The orthography here is totally screwing with the etymology and i just don't like it, not one bit.

For me, this is something of a double whammy: i've always thought it absurd to use a machine maker's name for the thing the machine produces and now i've got to use the name with a spelling that has no relation to it, whatsoever. The orthography here is totally screwing with the etymology and i just don't like it, not one bit.There's an Australian aboriginal character in one of Herzog's films who confesses that the reason he stopped speaking was because the slow genocide of his tribe left him with no one who spoke his language. Honestly, there are moments when i feel that way, a slow descent into a globalized transliteratory and mis-translational hell. In Hungary, hello is now part of the everyday language, which sounds graciously anglophilic until you realize they use it at the end of a conversation, not the beginning. i'll never get used to that, anymore than i will looking for a place to kseroks some documents. i'm all for diversity and mashing things up, world music and intergallactic web servers, etc. etc. but the words still have to mean something! Otherwise, our thoughts become temporally exclusive and watered down across cultural boundaries to the point where we're all negating our identities in order to communicate basically nothing. What would Homer say? Okay? OK? Okeh?

No comments:

Post a Comment